A Philosophical Method For Next Level Thinking

On the Next Brain blog we explore specific techniques for improving brain function and cognitive performance. We report on techniques from any field where excellence in thinking, learning, perception, memory, creativity, decision-making and other mental functions are known to take place. For example, consider the field of philosophy. Philosophers are known for their ability to think deeply and clearly about the most complex topics. What can we learn from them to enhance our cognitive performance?

One technique that you can pick up fairly quickly and use nearly every day is call the Toulmin Method. This is a method for analyzing text or verbal statements and abstracting any argument that is being made. Making the claim, reasons and justification for an argument clear is a key step in being able to think analytically about a topic rather than just going with our gut instinct.

Colorado State University has developed an excellent guide to The Toulmin Method. In short and simple language it breaks down the parts to an argument, explains how to see them in everyday circumstances and even provides a worksheet to apply the method.

It should take no more than 45 minutes to work through the site including the student example. You can pick a newspaper story, blog post, memo from work or passage from a book you are reading and try and apply it. Keep using it and you will see how the depth and intellectual clarity you have around key issues and arguments improves. You might even find yourself changing your mind on important matters!

Interested to hear from readers that use the Toulmin Method or any other technique for making arguments explicit and analyzing them.

Categories: Decision Making, Problem Solving, Training Tags: critical thinking

Build Your Brain By Making Better Arguments

Making formally sound and psychological convincing arguments is hard mental work. It is a form of critical reasoning and therefore practicing it is a great technique for improving your thinking (cognitive) skills. Argumentation and how to use it to improve cognitive performance will be a frequent topic on the Next Brain Blog.

Making formally sound and psychological convincing arguments is hard mental work. It is a form of critical reasoning and therefore practicing it is a great technique for improving your thinking (cognitive) skills. Argumentation and how to use it to improve cognitive performance will be a frequent topic on the Next Brain Blog.

We can learn how to make good arguments much as we can learn to make good food, music or art. It takes an understanding of the fundamentals of argumentation, tons of practice and taking on new and challenging situations regularly. Fortunately, the fundamentals of argumentation are clear, there are many opportunities to constructively practice at home, work and in the community and new challenges are presented to us daily.

Getting started in the art of argument requires a clear statement of the point you want to make (the conclusion) as well as a clear statement of what justifies it (premises).

Just writing down your premises and conclusion can be a difficult challenge but one that adds enormously to the clarity of thought.

A good argument is one where the conclusion can be logically inferred from the premises, is free of logical fallacies, anticipates and deflates counter arguments, has well-justified premises and clearly delineates factual claims from opinions.

For a great introduction to the ideas of formal and informal validity of arguments check out the post, What Makes a Good Argument? on the Thinking Matters Blog. It covers the 9 types for formal validity you are likely to use as well as 8 common informal mistakes you are likely to commit.

You can show that your argument is formally valid by demonstrating the conclusion (Q) follows from the premises (P) using one or more of the rules of deductive logic. For example, one rule is called modus ponens (and I quote from Thinking Matters):

“Modus ponens is Latin. It means “the mode which affirms”. Knowing the English translation makes it very easy to follow:

- P –> Q

- P

- Q

In plain English: if P, then Q; P, therefore Q. “P” and “Q” represent propositions, so it’s helpful to substitute in simple phrases for them, to get a better idea of what the rule is saying. For example, let P mean “it is raining”, and let Q mean “the ground is wet”. So:

- If it is raining, then the ground is wet.

- It is raining.

- Therefore, the ground is wet.

As you see, this is really a very simple and obvious rule—as you’ll find that all the fundamental rules of logic are.”

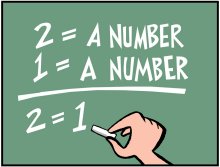

Formal validity is not enough. Your argument must also must avoid falling into a logic trap. For example, consider the argument from ignorance (quoting from Thinking Matters):

Formal validity is not enough. Your argument must also must avoid falling into a logic trap. For example, consider the argument from ignorance (quoting from Thinking Matters):

“Arguing that a belief is false because there is insufficient evidence for it.

- No one can disprove the existence of God. Therefore, God exists.

- There’s no evidence that the Red Sea was ever parted. Therefore, the account in Exodus is a myth. (Notice, though, that an argument saying that there is evidence that the Red Sea was not ever parted would not be fallacious.)”

I have heard many arguments made this way. It may take you an hour or so to work through all 17 principles and really understand each one. However, it is well worth your time. With a basic understanding you can use them as a quick checklist to refine the clarity, power and validity of your arguments.

I am interested to hear from readers that practice the art of argumentation and how it has impacted your effectiveness as a thinker.

Sources: Image of Thinking Cap, Image of Logical Fallacy

Categories: IQ and EQ, Problem Solving, Training Tags: critical reasoning, critical thinking

Critical Reasoning Sharpens the Mind But Takes Mega Effort to Develop

Thinking or reasoning critically is a key cognitive skill. It means we know how to question assumptions, see the logic or lack of logic in an argument, draw sound conclusions from evidence, find root concepts and causes, generate possibilities systematically, avoid decision traps and cognitive biases, see things from multiple points of view and otherwise rigorously deal with ambiguity.

Thinking or reasoning critically is a key cognitive skill. It means we know how to question assumptions, see the logic or lack of logic in an argument, draw sound conclusions from evidence, find root concepts and causes, generate possibilities systematically, avoid decision traps and cognitive biases, see things from multiple points of view and otherwise rigorously deal with ambiguity.

Critical thinking is so important that it has been a major area of focus since the time of the ancient Greek philosophers. But it is not just a philosophical thing. For example, in a recent post on the Harvard Business Review’s blog How Leaders Should Think Critically, the authors argue that it is a fundamental skill for today’s business leaders and students. Of course the same arguments apply to non-business school students and leaders as well as everyone trying to make their way in today’s complex society.

In short, enhancing critical thinking is an important option for anyone interested in building a sharper mind and will be a regular topic on this blog.

But how can you improve it? Self-study using a book or web resource is a good way. I’ll make a couple of recommendations below. You can also scout out a class or seminar at a location near you. For those who like a more guided approach, you can contract the services of a tutor or philosophical counselor.

No matter how you start please be sure to share your experiences with other readers of this blog.

For a good introductory text on critical reasoning see, Thought and Knowledge: An Introduction to Critical Reasoning. It is relatively inexpensive, easy to read and covers basic and advanced topics. It has a more psychological than philosophical orientation and provides nice chapter summaries. You can access it online on Questia here.

For a very comprehensive free treatment, check out Critical Reasoning a User’s Manual (version 3.0). It is a 640-page (3 MB) PDF. It is also available online in the document reader Scribd here.

Both these resources will take an enormous effort to get through! If you are aware of a better general introduction please comment on this post. In the meantime, I will blog on specific techniques that you can use to build critical reasoning skills with much less effort.

Categories: Ancient Ways, Books, Decision Making, Problem Solving, Training Tags: critical reasoning, critical thinking