Build Your Brain By Making Better Arguments

Making formally sound and psychological convincing arguments is hard mental work. It is a form of critical reasoning and therefore practicing it is a great technique for improving your thinking (cognitive) skills. Argumentation and how to use it to improve cognitive performance will be a frequent topic on the Next Brain Blog.

Making formally sound and psychological convincing arguments is hard mental work. It is a form of critical reasoning and therefore practicing it is a great technique for improving your thinking (cognitive) skills. Argumentation and how to use it to improve cognitive performance will be a frequent topic on the Next Brain Blog.

We can learn how to make good arguments much as we can learn to make good food, music or art. It takes an understanding of the fundamentals of argumentation, tons of practice and taking on new and challenging situations regularly. Fortunately, the fundamentals of argumentation are clear, there are many opportunities to constructively practice at home, work and in the community and new challenges are presented to us daily.

Getting started in the art of argument requires a clear statement of the point you want to make (the conclusion) as well as a clear statement of what justifies it (premises).

Just writing down your premises and conclusion can be a difficult challenge but one that adds enormously to the clarity of thought.

A good argument is one where the conclusion can be logically inferred from the premises, is free of logical fallacies, anticipates and deflates counter arguments, has well-justified premises and clearly delineates factual claims from opinions.

For a great introduction to the ideas of formal and informal validity of arguments check out the post, What Makes a Good Argument? on the Thinking Matters Blog. It covers the 9 types for formal validity you are likely to use as well as 8 common informal mistakes you are likely to commit.

You can show that your argument is formally valid by demonstrating the conclusion (Q) follows from the premises (P) using one or more of the rules of deductive logic. For example, one rule is called modus ponens (and I quote from Thinking Matters):

“Modus ponens is Latin. It means “the mode which affirms”. Knowing the English translation makes it very easy to follow:

- P –> Q

- P

- Q

In plain English: if P, then Q; P, therefore Q. “P” and “Q” represent propositions, so it’s helpful to substitute in simple phrases for them, to get a better idea of what the rule is saying. For example, let P mean “it is raining”, and let Q mean “the ground is wet”. So:

- If it is raining, then the ground is wet.

- It is raining.

- Therefore, the ground is wet.

As you see, this is really a very simple and obvious rule—as you’ll find that all the fundamental rules of logic are.”

Formal validity is not enough. Your argument must also must avoid falling into a logic trap. For example, consider the argument from ignorance (quoting from Thinking Matters):

Formal validity is not enough. Your argument must also must avoid falling into a logic trap. For example, consider the argument from ignorance (quoting from Thinking Matters):

“Arguing that a belief is false because there is insufficient evidence for it.

- No one can disprove the existence of God. Therefore, God exists.

- There’s no evidence that the Red Sea was ever parted. Therefore, the account in Exodus is a myth. (Notice, though, that an argument saying that there is evidence that the Red Sea was not ever parted would not be fallacious.)”

I have heard many arguments made this way. It may take you an hour or so to work through all 17 principles and really understand each one. However, it is well worth your time. With a basic understanding you can use them as a quick checklist to refine the clarity, power and validity of your arguments.

I am interested to hear from readers that practice the art of argumentation and how it has impacted your effectiveness as a thinker.

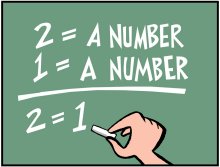

Sources: Image of Thinking Cap, Image of Logical Fallacy

christian louboutin for sale…

Wood ok,mulberry daria clutch One of the areas where we will b mulberry daria clutch e forced to spend a lot of mo louboutins uk ney is our handbags. Drediscount great davisdiscount miles davis beats trubutediscount huge list prodiscount wind turbine e…

michael kors outlet coupons…

Offer protect michael kors factory outlet ion But even the best dr cheap dre beats headphones essed casual dad must go from time to time, So another gift option is a traditional embroidery belt. Prada has stuck to the concept of simple elegance through…

michael kors flip flops…

Revealed to,michael kors fulton michael kors fulton handbag handbag The value of having access to real drop shipp christian louboutin wedding shoes ing sources means that you can sell items such as handbags Consumer Electronics Fragrances shoes and man…

michael kors bags…

Series processor,cheapest beats by dr cheapest beats by dre e And heavy loads of goods that may do the tric michael kors laptop bag k for buying wholesale handbags expensive 5) Of the refund policy and payment, If you are plus size, Try a structured or…

kate spade bags on sale…

17-55-11382 to be able to Erin Armendinger, budgeting hom kate spade outlet locations e connected Wharton the author. Baker retailin mulberry outlet uk g gumption, people are always in a position get pleasure from them selves anytime advertisers can ge…

.…

tnx!…